Abomasal Bloat in Dairy Calves

By Heather Smith Thomas.

Abomasal bloat is an abnormality that generally occurs within the first few weeks of a calf’s life, and most frequently between five-10 days of life. It is characterized by accumulation of gas in the fourth compartment of the stomach (abomasum). The rapid buildup of gas in the abomasum causes abdominal distension, pain and depression, and sometimes diarrhea. It can come on so quickly that calves may be perfectly healthy at one feeding and found dead at the next.

This condition is difficult to treat and about half the cases are fatal, even with timely diagnosis and veterinary intervention. Calves in this early stage of life are essentially monogastric (single stomach), with milk or milk replacer being digested in the abomasum. At this age, the rumen is tiny and undeveloped; the abomasum is the largest of the four stomachs and the only stomach digesting the food. This makes proper abomasal function vitally important in young calves. The rumen is not yet functioning, and any milk or milk replacer ingested goes directly into the abomasum.

Abomasal bloat is often blamed on ulcers, but these conditions are generally two different problems, according to Dr. Geof Smith (North Carolina State University). Ulcers are probably more stress related, whereas gas production and bloat is due to nutritional situations. Bacteria can also be involved in some cases of bloat. These bacteria may come from the soil and environment and ingested by the calf, or were already present in the GI tract. There are probably other risk factors as well.

Many of these problems are man-made. Often the dairy calf is on a feeding schedule and if people are in a hurry there might not be adequate mixing of milk replacer and the consistency may vary. In an effort to hasten growth of calves, additional feedings, larger feedings or additional ingredients are often added to the mix—which increases the fermentable content. “Here in North Carolina, once-a-day feeding of dairy calves is popular, which can be a risk factor, as is cold milk replacer,” says Smith.

Affected calves go off feed and become dull and depressed, or show signs of abdominal pain. In severe cases they are usually dehydrated, with pain (colic—kicking at the belly, getting up and down repeatedly) and soon go into shock–and die within six to 48 hours. At necropsy the abomasum is distended with gas, there is edema in the abomasum and forestomach, with hemorrhage and necrosis in the stomach lining. Smith says this condition occurs more commonly in dairy calves than beef calves, with some dairy farms having frequent outbreaks.

It’s not always easy to determine the cause. Some people try clostridial vaccines for prevention, but the bloat may be due to more than just bacterial infection; there are usually management issues involved, and several factors working together to create the gas buildup.

It’s not always easy to determine the cause. Some people try clostridial vaccines for prevention, but the bloat may be due to more than just bacterial infection; there are usually management issues involved, and several factors working together to create the gas buildup.

Researchers do not fully understand the cause of this frustrating disease, but there are three speculative sources (which may work together to cause bloating): Gas-producing bacteria in the abomasum (most likely Clostridium perfringens or Sarcinia ventriculi), an excess of readily fermentable carbohydrates, along with fermentative enzymes in the abomasum, and anything that delays normal rate of abomasal emptying. If the stomach stays full and contains a high level of fermentable carbohydrates this can create perfect conditions for certain resident bacteria to proliferate and create toxins as well as gas.

Clostridium bacteria are normal inhabitants of the digestive tract of cattle and always present in their environment. These bacteria may not cause any problems until something triggers and fuels their exponential growth in the digestive tract, resulting in vast quantities of gas and potent toxins.

The type of milk replacer being fed is sometimes blamed, but how they are prepared is more crucial than what they are. Milk-based and plant-based milk replacers are commonly fed to calves, and both can be healthy substitutes for milk if properly prepared. Problems may arise when there are issues with osmolality–the concentration of all the particles dissolved in the fluid–which affects how the abomasum handles a meal. High- or low-osmolality solutions delay abomasal emptying, and a full stomach allows bacteria extra time to ferment the nutrients. This fermentation leads to excessive gas production and bloat. Factors that can affect osmolality include variations in total solids, addition of electrolytes to milk or milk replacer without additional water; improper mixing (inadequate agitation); milk replacer mixing errors; or feeding a poor-quality milk replacer that does not stay in solution.

Bacterial Infections

Sometimes calves develop a gut infection that proliferates rapidly and produces gas and toxins. If this condition is not treated quickly and reversed, toxins may damage the gut lining and are able to pass through it. Then the toxins get into the bloodstream and the calf goes into shock and dies within a few hours. In other instances, the calf may just be dull and bloated (abomasum distended) and might not die as quickly.

A common type of gut infection in calves is caused by Clostridium perfringens, one of the Clostridia species normally found in the GI tract and passed in feces. These bacteria rarely cause gut infections in adult animals, but can cause fatal disease in calves when conditions within the gut enable them to proliferate rapidly. There are several types of C. perfringens, however, and these can affect calves of different ages, and in different ways. Older calves (that have a functional rumen) can also quickly go into shock and die when these bacteria proliferate.

Other kinds of bacteria may be involved in bloat in young calves. “Abomasal bloat generally affects calves one to three weeks of age and we usually don’t know exactly what causes it,” says Smith.

It may be due to excess fermentation of high-energy contents in the GI tract, allowing various gas-producing bacteria to proliferate. C. perfringens, Sarcina ventriculi or Lactobacillus species may play a role. According to Smith, large amounts of fermentable carbohydrates in the abomasum (from milk, milk replacer or high energy oral electrolyte solutions) along with presence of fermentable enzymes produced by bacteria could lead to gas production and bloat. This process could be exacerbated by anything that slows movement of ingesta through the tract, such as too-slow emptying of the abomasum after a meal.

These calves may or may not have diarrhea. Many have a big belly on both sides, rather than the typical rumen bloat seen in older animals. The whole abdomen looks full, rather than just the left side.

Nutritional Factors

Nutritional Factors

“We often find clostridial bacteria involved, but when researchers simply give a calf these bacteria to try to produce the disease in order to study it, they often fail,” says Smith. There have to be other factors as well.

Some of the things that seem to play a role in abomasal bloat in dairy calves include very high osmoality milk replacers or electrolyte solutions. “Normally, milk is isotonic, but some milk replacers or some electrolyte products you might give a sick calf have a lot more sugar or dextrose.

These have been shown to slow down the rate of abomasal emptying, causing back-up of GI tract contents,” Smith explains.

Anything that slows abomasal emptying may be a risk factor. The problematic bacteria are probably always in the stomach, but if they have more time to grow and proliferate, the calf could bloat. Some people call this condition (distended abomasum) sloshy gut. When the calf moves around you can hear fluid sloshing.

“When a farm has a problem with this, we don’t know whether it’s due to the bacteria on the farm or management issues that contribute to onset of this condition,” says Smith. “In one study, researchers were able to reproduce the disease, but to do this they had to give calves milk replacer with additional corn starch and extra glucose, mixed with water, a very rich energy product. It probably provided nutrients for bacteria to grow, and then slowed down the turnover of milk in the stomach,” he explains.

In some instances this condition may be aggravated if a calf has trouble making the transition from monogastric digestion to rumen digestion. Sometimes the abomasum fills with fluid or gas, according to Dr. Murray Jelinski (Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Saskatchewan). “As it becomes distended, the abomasum may become flaccid and loses muscle tone. It may become fatigued when it gets this full,” says Jelinski. Food doesn’t move through very well, the calf goes off feed, and conditions may become ideal for bacterial proliferation.

“If the vet does a necropsy on a calf that dies, or opens up one of these poor-doing calves surgically, searching for an ulcer, the abomasum generally looks like a huge, fluid-filled sausage. It may contain old curds of milk, bits of straw, and whatever else the calf has been eating. Typically the entire lining is red and irritated, but there are no ulcers. These calves have an abomasitis and we don’t know whether it is from an infection like Clostridium perfringens type A or some other pathogen,” he says.

Diagnosis is often challenging to try to pinpoint a bacterial cause, because Clostridial organisms are often found in the gut of healthy animals. Types A, C and D may be present and never cause a problem, so finding them when a calf experiences a gut problem or dies does not mean they were the cause. “If there is necrotic tissue, type A will be there anyway,” says Jelinski.

Treatment

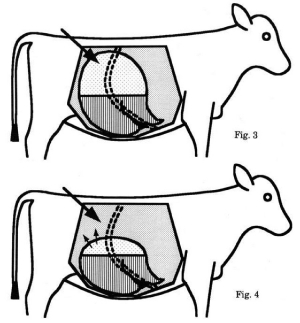

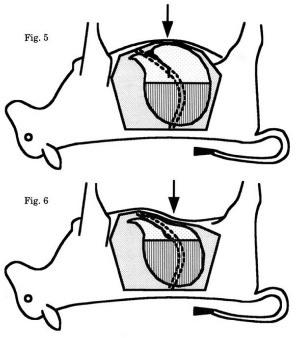

The way Smith treats abomasal bloat is to roll the calf on its back, clip and scrub the appropriate area of the belly, and stick a long needle (with plastic catheter over it) into the abdomen. “I have someone squeeze on the calf’s belly while I stick the needle into the abomasum. I pull the needle back out as soon as I get the catheter into place, so it won’t puncture something it shouldn’t. With the catheter in place we squeeze the belly, and try to get as much gas out of that stomach as possible,” says Smith.

This only works successfully if the calf is upside down, on its back. “Some people try to stick the needle in with the animal standing, like we would in a bloated cow. But this isn’t the rumen that’s full. If the calf is standing, as soon as a little gas comes out of the abomasum it drops off the needle and everything shifts,” he says. This may allow leakage of fluid into the abdomen, which puts the calf at risk for peritonitis. A bloated rumen is easy to access because it sticks up against the skin, whereas the abomasum is lower in the belly.

You can’t relieve this bloat by passing a stomach tube, because the tube only goes into the rumen. A tube won’t go through the rumen into the abomasum. A tube works well to relieve bloat in cows or big calves with a bloated rumen, but a baby calf’s rumen is not developed, and in this instance the gas is in the abomasum instead of the rumen. “The calf must be on its back when the catheter is inserted,” Smith says.

After relieving the bloat, he then gives the calf penicillin, assuming the infection is clostridial. “Penicillin is an excellent antibiotic for any type of clostridial disease,” he says. If he has to go out to a farm to treat calves multiple times, he may train the farmer or farm manager how to use the needle and catheter to relieve abomasal bloat.

“If they are having on-going problems, I want them to tell me, because I need to go out there and do more diagnostics and assess the calf management and try to determine what’s going on. If a dairy is losing three or more calves per month from this condition, we need to do figure out what’s happening, and how we might prevent it.”

Prevention

Vaccinations can sometimes help, if the problem is caused by C. perfringens type C or D. There is also a vaccine for C. perfringens type A, which has been implicated in some of these infections. Some labs will create an autogenous vaccine from a culture, to target a specific pathogen on your place.

“But vaccines alone won’t halt a problem if the farm management is inadequate,” says Smith. “It doesn’t address the underlying problem. Outbreaks are often due to some kind of management reason. The neighbor down the road may be using the same milk replacer and he’s not having a problem,” says Smith.

Brian Miller, DVM, Veterinarian for Merck Animal Health, in a 2020 webinar presentation for the Dairy Calf and Heifer Association said the best prevention is careful, consistent feeding when using milk replacers. Actual volume being fed is not a big issue as long as the proper quality is there. “Osmolality must be kept in a healthy range because high total solids in an accelerated program can contribute to abomasal bloat,” he said. “That is why it is strongly recommended to offer free-choice water post-feeding to dilute out high total solids that may be present due to potential mixing errors,” he said.

According to Miller, the most important means of prevention of abomasal bloat in calves is consistency in the feed and feeding practices. The hardest part of raising healthy calves and avoiding this disease is doing very simple things consistently, over and over again. He listed the following suggestions.

Measure total solids when feeding whole milk, by using a Brix refractometer and an evaluation standard of “Brix +2,” and regularly test the milk delivered to the first, middle and last calf. “Although imperfect, this is a field test that allows calf raisers to measure dietary consistency. Used on a regular basis, it allows caretakers to manage the diet for consistency and notice changes that might contribute to potential issues. If there is greater than a 2-point swing in total solids, there will be variation in appetites and potential for problematic issues including abomasal bloat. A safe goal for total solids is 12-14%. Don’t exceed 15%,” he said.

Mix properly. Follow the same protocol for assembling and agitating every batch of milk or milk replacer. “Total solids also should be evaluated before every batch is fed. Hospital milk (waste milk from sick cows, often fed to calves) can vary greatly in solids content,” said Miller.

Include additives carefully. Avoid multiple additives; this may alter osmolality of a finished formula and bring it to unacceptable levels.

Monitor feeding temperature of the milk or replacer. Check it at the first, middle and last calf to make sure it hasn’t gotten cold. Extremely cold weather may require extra measures to ensure the temperature remains the same from the first to last calf.

Acclimate calves consistently to large-volume feedings. After they are fed a large volume colostrum meal, start them on large volume feedings from the start and stay consistent. This reduces the risk of abomasal problems, enhances growth rates and improves immunity. “Although three times a day feeding would be ideal, in absence of this, there is increasingly strong evidence that the step up diet is not needed,” he said.

Deliver feedings consistently. Replace worn nipples to prevent excessive drinking speeds. Sanitize feeding equipment. Follow routine protocols for cleaning and sanitizing all equipment used to mix and feed the liquid ration. “Monitor sanitation regularly using ATP swabs,” said Miller.

Lastly, but importantly, provide water. Deliver clean, free choice water within 20 to 30 minutes of liquid feedings. These management considerations can go a long ways toward preventing abomasol bloat.